Chlo Ashby explores six artists and writers who have found inspiration in isolation.

I paint myself because I am often alone and I am the subject I know best. So said Frida Kahlo, an artist who drew on personal isolation and suffering in her penetrating self-portraits. She experienced chronic pain after getting caught up in a horrific traffic accident as a teenager. Emotionally she was tormented by her turbulent relationship with her husband, the renowned muralist and philanderer Diego Rivera. As others have done before and after her, she took the feeling of being bruised and alone and turned it into great art. Here are six other artists and writers who have found inspiration in isolation.

Vivian Suter

Suter rarely leaves her hideaway in the Guatemalan Rainforest. The Swiss-Argentine artist was born in Buenos Aires in 1949 and, after moving to Switzerland with her parents, spent her teenage years and the start of her career in Basel. She was beginning to make her mark as an abstract painter when she decided to travel through Central America in the early 1980s. She ended up settling in the small lakeside town of Panajachel in rural Guatemala.

Suter has two studios on a hillside, high above the treetops, and in her garden but she prefers to paint outside, accompanied only by her dogs. She's inspired by the tropical plants, birds and wildly unpredictable weather conditions of her adopted home. Free from distractions, she works quickly and freely sweeping, splattering and smudging paint onto unstretched and unprimed canvases.

In 2005 swathes of Panajachel were devastated by a tropical storm, which flooded her garden studio a white barn in which she stores her work. Instead of tossing away the battered sheets of canvas and starting from scratch, Suter made a choice: from then on, she would embrace her environment, however volatile. Today, when she finishes a painting, she either buries it or leaves it outside to weather welcoming water marks, dried leaves, specks of mud.

Tara Westover

From the Guatemalan Rainforest to a jagged little patch of Idaho. Westover may not have sought out isolation as Suter did, but it inspired her nonetheless. The author was the youngest of six siblings and grew up on a remote homestead in the mountains preparing for the End of Days with survivalist Mormon parents. She was nine years old before she got a birth certificate and her father's distrust of doctors meant she didn't have any medical records. When she was 17, she turned to books and education as a means of escape and a decade later she had completed a PhD at Cambridge.

Educated (2018), a memoir that's so beautifully written and briskly paced it reads like fiction, tells Westover's story from salvaging scrap in her father's junkyard to making tinctures with her midwife mother, being abused by one brother and encouraged by another. She seeks solace from her isolated childhood in education, and she succeeds, but in the process she becomes estranged from her parents and half her siblings. By the end of the book, she's what she calls a changed person. You could call this selfhood many things, she writes. Transformation. Metamorphosis. Falsity. Betrayal. I call it an education.

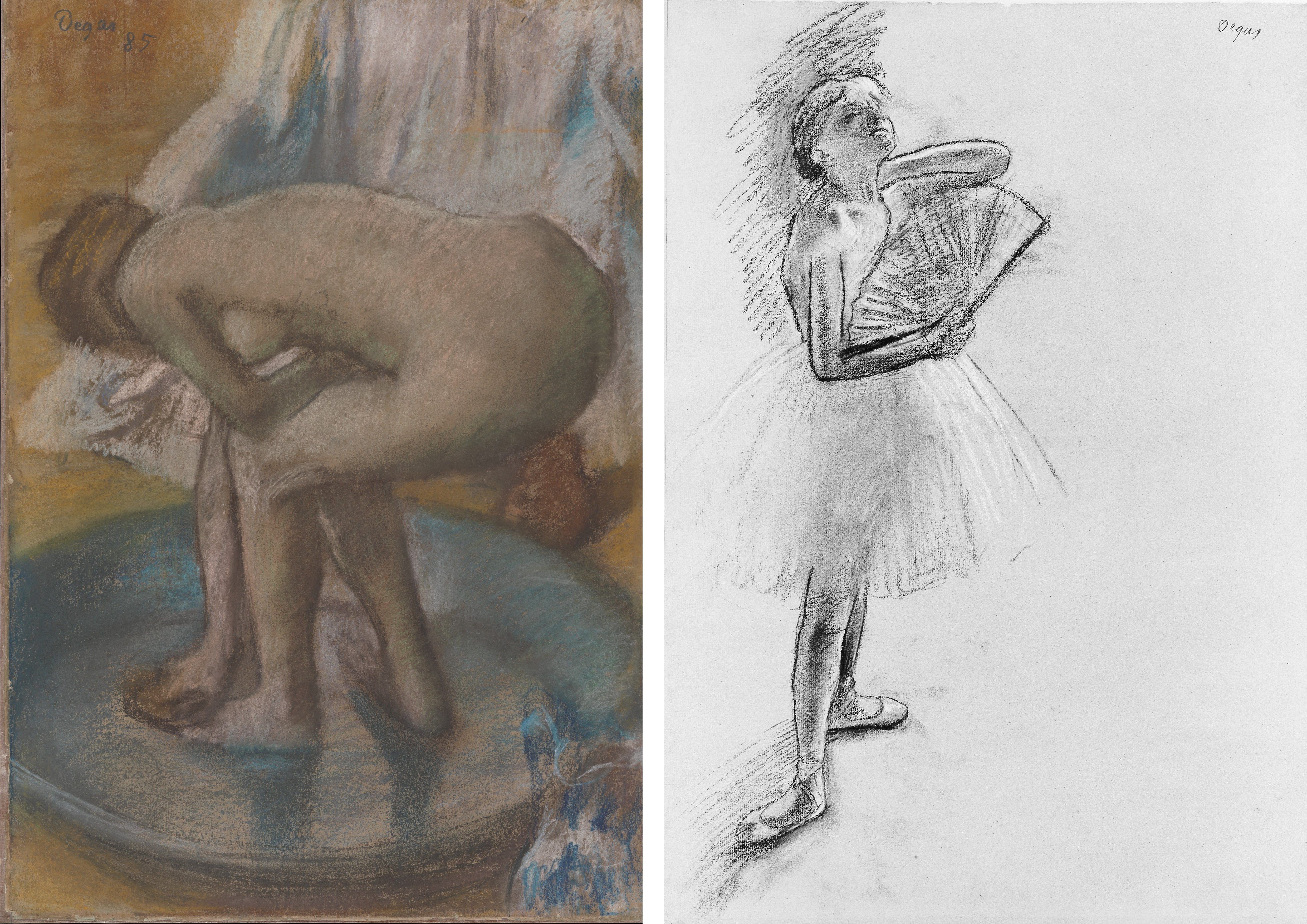

Edgar Degas

From ballet dancers and bathers to milliners and laundresses, Degas loved to paint working women. Whether dancing or ironing, he was interested in the way they stood, the way they moved their bodies. And more often than not, he depicted them alone paying tribute to their concerted efforts and isolation.

Like his contemporaries, the 19th-century artist was a keen observer of modern life, but he was less interested in the stories of the women he represented than their repetitive labour. He portrayed ballerinas practising their positions and laundresses dragging hot and heavy irons across freshly washed fabrics. Even if he sketched one while others were in the room, he would home in on her body, capturing it up close and at an oblique angle, forging a sense of solitude.

When he turned to nudes, Degas was tapping into an age-old tradition of pinning down on paper female flesh. In his candid studies of women sponging themselves or towelling off after a bath, the apparent lack of self-consciousness at play suggests that the subjects seemingly caught in private are unaware we're watching.

Sylvia Plath

Plath had made a name for herself in literary circles by the time she killed herself at the age of 30. Her autobiographical poems explore mental illness and the malaise that haunted the US in the postwar period. Her only novel, The Bell Jar (1963), is also partly based on her own life and the sense of isolation brought on by her depression.

The narrative follows Esther Greenwood, a bright, young woman who is, she tells us, supposed to be having the time of my life. Like Plath, she wins an internship at a glossy New York fashion magazine in 1953. But Greenwood is too driven, too neurotic, and in the blistering summer she finds herself slipping slowly into despair and ultimately attempting suicide more than once. Surrounded by strangers, she feels more alone than ever.

What I've done is to throw together events from my own life, fictionalising to add colour it's a potboiler really, but I think it will show how isolated a person feels when he is suffering a breakdown, Plath told her mother. I've tried to picture my world and the people in it as seen through the distorting lens of a bell jar.

Edward Hopper

No artist captures urban isolation like Hopper, the 20th-century American artist whose striking paintings tap into that particular strain of loneliness that flourishes in a city and creeps up on unsuspecting individuals surrounded by strangers the fate of Plath's protagonist. He portrays men and women either entirely alone or gathered together in blankly silent groups.

In Nighthawks (1942), four figures are shown in a floodlit diner at a lower-Manhattan intersection: an employee, a couple and a man drinking his coffee alone. No one is talking. Even the couple are uncoupled: he stares grimly ahead while clutching a cigarette; she fiddles with a folded dollar bill. The gaunt waiter grimaces. The lone customer has his hunched back to us. The empty bar stools highlight the sense of isolation, as does the empty glass. Out on the street, there's nothing but shadows. The empty shopfront opposite looks abandoned. Hopper paints lost souls and, in doing so, makes us consider our own sense of solitude.

Ocean Vuong

It was while studying at Brooklyn College in New York that Vuong began to pen poems by night. He relished the sense of isolation and found he was less critical of himself, his inner critic at bay (or already gone to bed). When he was two years old, he and his family fled from Vietnam to the US and resettled in Hartford, Connecticut. None of them spoke English and soon his father left. Vuong was raised by his mother and grandmother, both of whom are at the heart of his debut novel On Earth We're Briefly Gorgeous (2019).

A work of autobiographical fiction, the novel is a letter from a son to his illiterate mother a gesture both intimate and detached. It tells the story of Little Dog, a Vietnamese refugee trying to make a life for himself in the US while grappling with family trauma, brutality and his love for an ill-fated boy called Trevor. Vuong too grew up in a violent household and has witnessed discrimination as a gay Asian-American poet. From the margins he has created a marvel, a lyrical exploration of masculinity, race and courage.

Words by Chlo Ashby.

Image Credits: Portrait of Vivian Suter by Flavio Karrer. Installation: Vivian Suter, Tintin's Sofa, Camden Arts Centre, 2019. Photo: Luke Walker. Portrait of Tara Westover by Paul Stuart. Portrait of Ocean Vuong by Tom Hines.

Add a comment