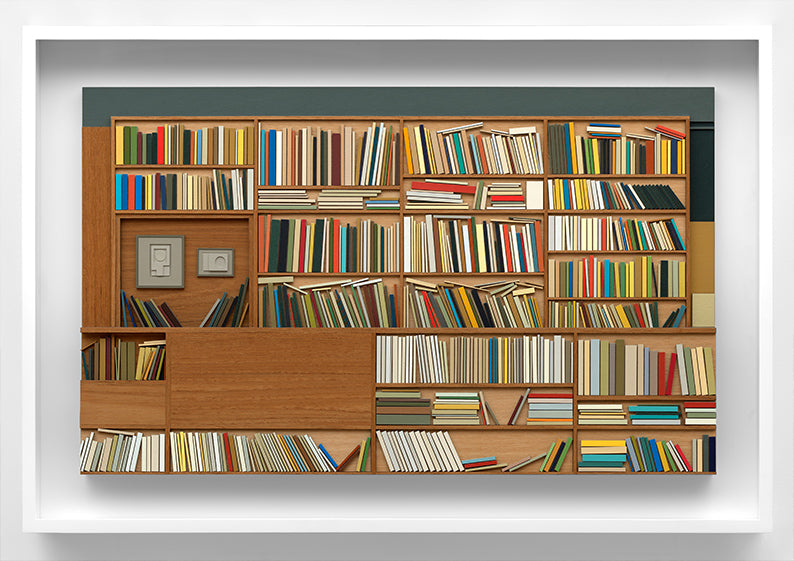

Lucy Williams is an artist - a successful artist in mid-career, represented by good galleries on both sides of the Atlantic - who makes collages. Or are they bas-reliefs? The Americans call them bas-reliefs,' she says, but I just call them collages.' So, to be more precise: they are figurative, layered collages mostly depicting aspects of modernist buildings. Theyare detailed, precise, crafted and painstaking to such an extraordinary degree - an extraordinary degree - that she is only able, working on them full time, to produce perhaps four works a year.

A superficial glance might register these pieces as very handsome architectural models but a closer looking will reveal the rendering of light, of reflections, of depth, of varying degrees of transparency. These works, as wellas being meticulous and analytical, are full of light and life - and all these qualities taken together manifest in an unlikely, haunting beauty.

We met and talked for an hour or so - firstly, about thelong road by which an artist arrives at her own true form of expression - in Lucy's case, such a very particular one - and, having arrived there, knows without doubt that this is where she is meant to be.

It took me a long time to realise I'm not a painter but I'm not really a sculptor either, I'm somewhere in between. It just took a long time to get there.'

Lucy first spent three years at Glasgow School of Art:I started off in sculpture but wasn't happy there and knew I'd made a bad decision. I ended up in painting - becausethat department was the most sympathetic.'

Glasgow allowed Lucy to experiment - making large oil paintings, striated colour fields depicting the fall of light onto flat surfaces. She credits the School for allowing her to see, coming as she did from a straightforward working class background, that to make a life as an artist was a realistic possibility.

After Glasgow she painted and drew for four years, supporting herself - as she did throughout her studies - with secretarial work. Then, knowing she needed a change of artistic direction, she applied for a three year post-graduate course at the Royal Academy Schools. The RA Schools take talented artists with a view to helping them develop. They admit only a handful of students each year - and the course is free, obviously a great advantage to a young artist.

I knew that I needed to sort my practice out and try to figure out what was going on. I needed to unpack things so, in a way, I was the perfect person going to the perfect course. But Ihad a really difficult time my first year - because I knew I had this job of figuring out what... it was. I knew that there was something - but I didn't know what it was.

So I was still painting when I first went - because that's what I did - and then I started painting on different materials like board and wallpaper and stuff. I decided not to be too hung up on things looking like other things so I explored... I was interested in Patrick Caulfield, I explored that whole territory: the idea of the outline, the paint inside, how he depicts light - he has a light and it's very creamywhite and then he has a dark space. I still think about that - about how to depict light in a graphic way.

And then I stopped painting and just made stuff outof different materials, flat - making collage in a more traditional sense, marquetry, putting stuff together using humble materials: paper and card, kraft paper, corrugated card - things you might use for packing.

And, as I started doing that - it took on its own life. I thought, this is really interesting - and I just started exploring. The collages became a little deeper - then I might put a hole in the board - or I might start a piece and thengo back a bit so I could put something in the background. It quite organically grew.

Architecture was always there - I'd take images of spaces around me and then make these constructions. They started off very simple and then became more complex. And asthey became more complex I went out and researched - and through the research it then became apparent what I was interested in, these modernist constructions.

It's still developing, all the time. I go with it on journeys- but I try not to be too het up about where it's going. Sometimes I look back and go - oh, that was a bit of a weird period. But I just go on the journey. I try, all the time, to revisit things that I was interested in and, say, make something that I thought was going to be the same as something I did five years ago - but it isn't. I just let the work take me on journeys, exploring.'

Throughout our conversation I was impressed by Lucy's clarity of thought, her practicality. Though she might not have known where her art was taking her, she understood where best to put herself so as to find out. We fell to talking about the making of the art.

I'm quite analytical. I don't really have romanticised views of what I do. I'm making. I make stuff. It comes out of the making.'

And surely it does: from the entire absorption into a months' long process of both deep looking and meticulous crafting: the making of a full sized, pencil drawing; the choice and painting of materials; the cutting of the different elements and their building in place. A tiled surface might be rendered in over a thousand tiny tiles of painted card, each less than a square centimetre in size, and every one -due to the demands of perspective - differently shaped from every other. The cutting out of these tiles alone might take six full weeks.

I asked about beauty in the work and Lucy says, I don't think I'd do it if I didn't like beautiful,' but says it in a slightly non-committal way, as though beauty is all well and good but isn't necessarily the object of the exercise. Then, with more enthusiasm, I do like difficult. A lot of the subject matter can be difficult - it isn't lovely; the buildings can be difficult, they're not pretty. But I am interested in finding the beautiful - in really going in and, you know, micro-looking at this stuff.'

I comment on how, even though she is using a thousand tiny pieces of inert material, she manages to catch something as fugitive as light.

That's the thing... the overriding thing is that, to try to bring the light into it. This is the trouble with collage - one needs to find a way to breathe a bit of life into it.'

We talk of artists she admires. As artists often do, Lucywill look with interest at the way other artists deal with particular problems that concern her in own work - as she looked at the way Patrick Caulfield dealt with light. But when I ask specifically about whom she likes - a long pause, then It's difficult... because I tend to look backwards. Bauhaus, Moholy-Nagy and Constructivism. I find Ben Nicholson quite interesting. Victor Passmore.' And then, with real enthusiasm, But I tell you who I love - love, love - is Mary Martin. I find her whole thing quite fascinating. Perhaps because she's a woman, as well. Lovely work, very considered and complete.'

The conversation moves away from specific artists and naturally back to her enthusiasm - the making:

The idea of the hand-made is really important in my work. Everything is hand painted, most of it is hand cut, because it's that thing - when you look at a Mondrian in a book and then you go and see one, you've got this line that is just wobbling slightly and, you know, the paint is a little cracked or the thing just doesn't meet - all that is really important. And it's completely lost in most reproductions. And it's that that I think is really important. You look at my work and you might think - wow, that's perfection - but it isn't. It's real too. It's important that that is there - that that tension remains.

That thing that people think you can make them by making a plan and it all just fits together - but that's not how they're made. They're made like paintings - I'm putting things on and then they come off again and then... things change quite a lot as they're being made. Though it seems as though everything has a beginning and an end, it doesn't. There's a lot that can change in a piece as you're making it.'

It's a great thing - a sly beauty achieved not by chasing it but by a slow and absorbed looking, a slow and absorbed making, a catching of the light, a love of the marks that the human hand makes. Art is never just a finished object, it's the record of a human process - thought and action, body and soul.

lnterview/writing by James Seaton. Photography by Arianna Lago. Lucy Williams is represented by Timothy Taylor, London.

Bookcase & Community Pool, 2016. Image courtesy Lucy Williams and Berggruen Gallery, San Francisco.

Add a comment