The plan had been to meet in person. To go to the house in Ham, south-west London where interior designer Tamsin Saunders and her artist daughter, Freya Marton have painstakingly built a shed studio at the end of the garden which is a feast for the eyes. But life had other ideas; my own daughter was unwell, and so it was over a video call that I spoke to Tamsin and Freya, and I couldn’t have asked for subjects more sensitive to the circumstances. Home design is what they do, but homes that are designed to accommodate “the beautiful chaos of life”, considerate of how the people within them live and grow, how plans change and how lives evolve.

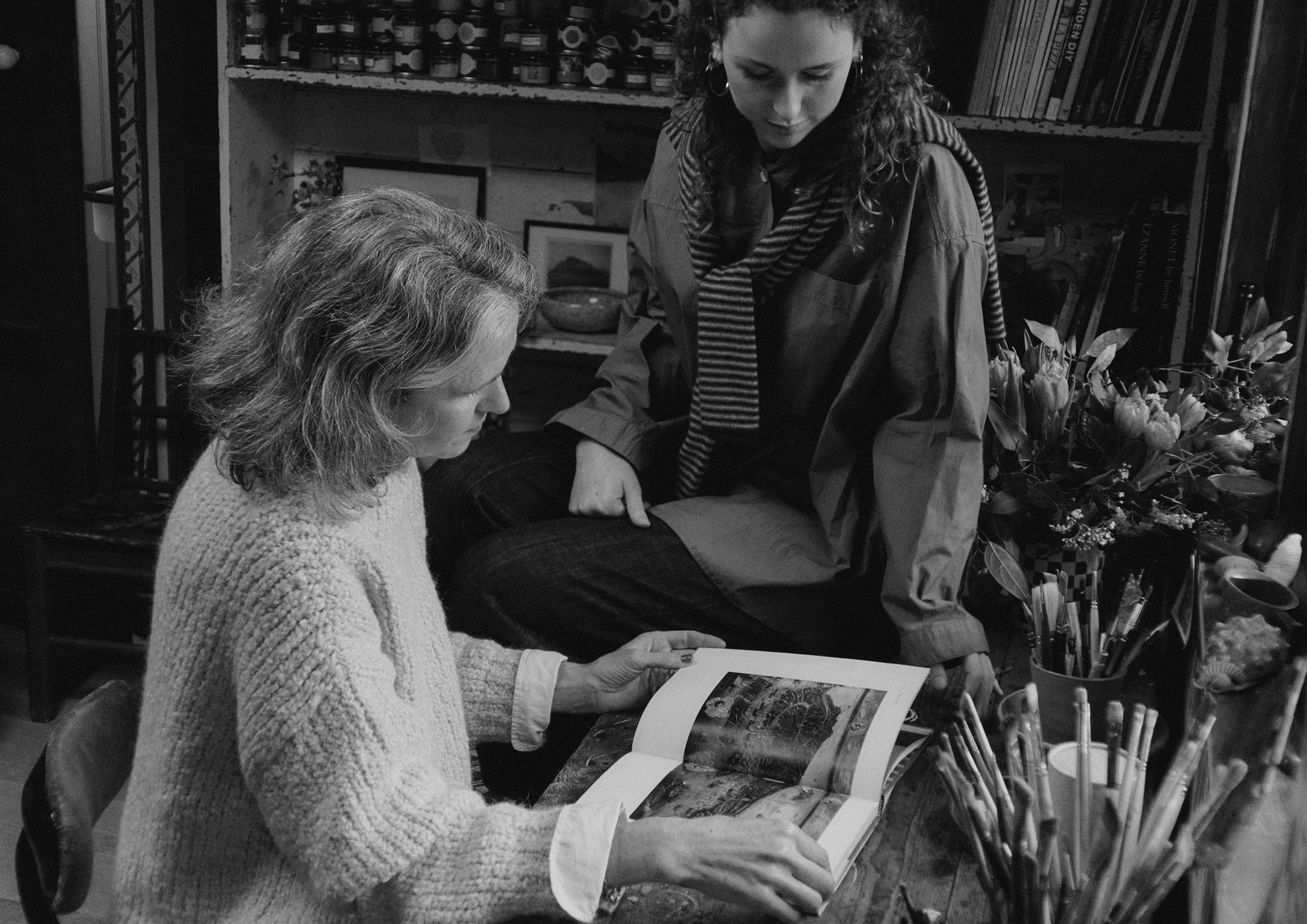

“I love homes that make you feel like you’re walking into a life, not just a house, discovering and seeing things that you haven’t seen before and learning more about the people who live there,” says Tamsin. She always gets to know the people for whom she designs interiors with her business Home and Found, honing in on the things which feel unique to them in order to tell their stories through their surroundings. “We’ll often start with something like a painting or textiles from their travels that they have had stored away for ages in the attic, or a piece of furniture that they’ve inherited,” she says, “I want a home to be a place which feels as though it has grown with the lives of those who live in it.”

That has certainly been the case in her own home. When we speak, she and Freya are sitting on a bench upholstered with a vintage ikat in their kitchen. It is a room which I can see is flooded by natural light, full of art, records and books and where plant life is as at home as the furniture – “the garden is my favourite room,” says Tamsin, “I’m always trying to break down the boundaries between inside and out” – and where things are thoughtfully positioned, but not preciously so. “Nothing screams ‘expensive’, I just like things which quietly sing of simple, understated beauty,” – such as a William Morris chair she found left out on the street when a neighbour was having a clear-out, and an Edwardian wing back chair from a house clearance in Marlow.

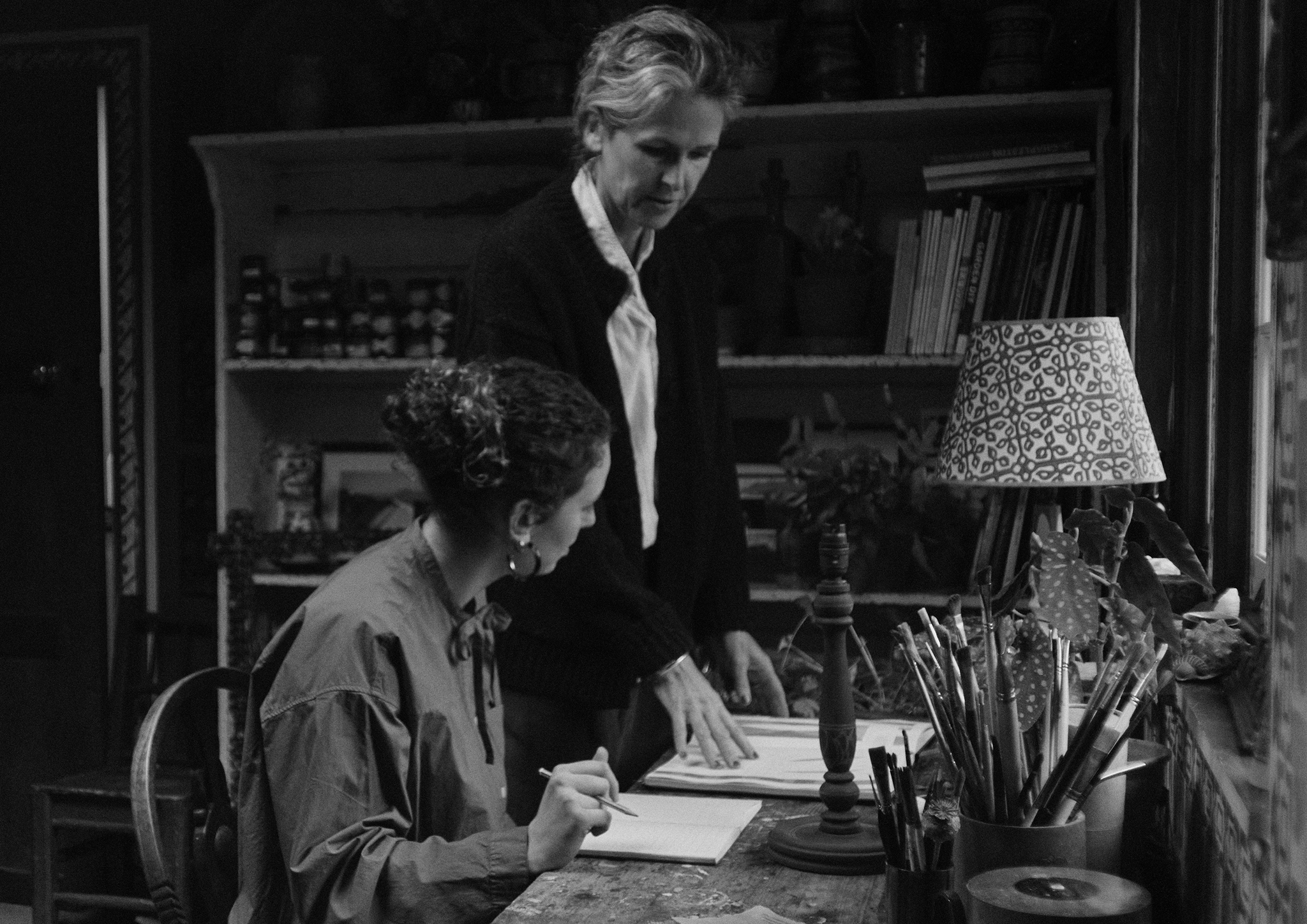

The Shed was an opportunity on several levels: for Tamsin and Freya to work together; to develop a space that was greater than the sum of its parts – and to blend their respective styles into something unique and original to their partnership. It was also a project that liberated them from any perceived ‘rules’, “I was restricted in what I could do with the house,” says Tamsin, “but with the Shed we could really do anything.” And they did. Built around a mature chestnut tree using reclaimed wood and found and ‘rescued’ pieces and furniture, the result is a case study in ‘more is more’, a deliciously rich orchestra of earthy hues, myriad patterns, antique finds including a 19C wooden cupboard, East African basketry bowls and shelves from an old bakery crammed full of books, paint pots and brushes, ceramics and natural treasures.

It took over three years to complete the Shed, and it all started in the pandemic, when Freya, then a first year student in Fine Art at Newcastle university, was forced to moved back home and work from her bedroom. “I love to procrastinate” she says “so I just started painting everything in there – the shelves, the wardrobes, the lamps – with patterns.” Realising she needed more space in which to work, Tamsin suggested she use one of the rooms next to her studio above her late partner Simon Cherry’s pub The Carpenter’s Arms in Chiswick and Freya’s business was born. To this day, her studio remains there – Black Lion Workshops, named after the backstreet it calls home.

Freya’s ‘obsession’ with pattern was later put to work in the Shed where Tamsin encouraged her to cover the walls in over a dozen different intricate patterns, inspired variously by things seen in nature, seed heads collected from the garden as well as details Tamsin and Simon spotted on their travels - the carved stone walls of the Alhambra, and details in medieval paintings and churches. The dominant pattern, however, is a soft clay-brown shield printed using potatoes - a technique which saw Freya frequently foraging in the fridge in search of ideally-sized replacements.

The unevenness and imperfections of the shed are key to its feeling not only rooted in the garden but of having grown from Tamsin and Freya’s experience and imaginations. Both women are clear that ‘undoneness’ is a key tenet of their approach. Just look at nature, they both say. “People ask me if things work together,” says Tamsin, “different patterns, colours and textures, and I just say look outside. There aren’t any rules in nature.” In the summer, they tell me, you can’t see the Shed at all, concealed as it is by fig and apple trees, and the garden in bloom. “I wanted it to be a hideaway,” Tamsin goes on, “so there’s no wi-fi in there. I loved the idea of it being a bit like a Japanese treehouse, or a thick, mossy Tolkeinesque retreat, for there to be a sense of seclusion.” I get the impression that quietude is important for Tamsin – now, especially. Though they had known each other since the mid-nineties, she and Simon had been together for just eight years when he died last August. Love and loss pulse gently through our conversation.

Tamsin says she spotted an opportunity in Freya’s vibrantly painted lamps, knowing she could use them in her clients' homes. She encouraged Freya to source the stands in markets and on eBay, customising them into one-off pieces for bedsides, a far cry from the “ubiquitous pairs of lamps” you see elsewhere. “I don’t want to make anything that’s going to make the world a more cluttered space,” Freya tells me, “and I’m not interested in copying anything. Mum’s ingrained that pretty hard”. I ask if there is ever any creative tension? “Freya’s much more precise than I am,” Tamsin says, after a pause, “I was a bit too slapdash for her when I tried to help with the potato printing in the Shed.”

It feels like no coincidence that the pocket between Hammersmith and Chiswick – where both mother and daughter have their studios – has always been a hub for creatives associated with the Arts and Crafts movement – such as Emery Walker and William Morris. Many influences imbue Tamsin and Freya’s work, from Californian sculptor JB Blunk and artist Anthony Gormley to Cornish churches and Austrian architect Josef Frank, whose textile designs have featured in another recent project. Both women seem to be magpies as much for objets d’art as they are for ideas.

One idea really stays with me – what Tamsin described as “the temporality of materials” – “things that people made with love and care. The people might be gone, but the things they made or found remain.” I understand this to be especially poignant for Tamsin now, just six months after losing Simon. The Carpenter’s Arms and the home they made together continue, their parts telling a story that is at once full of joy and sadness. 'Be lovely to meet you in the flesh, she writes to me later on, do let me know if you would like to come to the pub - it is a ruby in the dust - just like Simon. He was the magic.'

Freya wears the TOAST Tie Neck Cotton Poplin Shirt, Stripe Wool Cashmere Neat Sweater and Annie Organic Denim Full Length Jeans.

Tamsin wears the TOAST Boucle Alpaca Wool Sweater and Donegal Wool Knitted Jacket.

Words by Mina Holland.

Photography by Jessica Ellis.

Add a comment

2 comments